- Home

- Marie Arnold

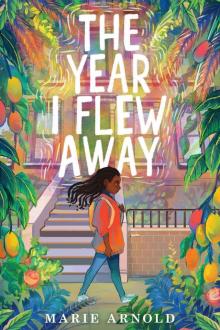

The Year I Flew Away

The Year I Flew Away Read online

Contents

* * *

Title Page

Contents

Copyright

Dedication

The River That Wasn’t There

Lady Lydia

If Only

Pale

Prospect Park

Almost Like Magic

Witch Hunt

Problems

In the Dark

Shout!

Pure

Apple Pie

Home

Be a Tomato

FEAR

Only Hope

Friends Like You

American

Epilogue

More Books from Versify

About the Author

Connect with HMH on Social Media

Copyright © 2021 by Marie Arnold

All rights reserved. For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to [email protected] or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

Versify® is an imprint of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

Versify is a registered trademark of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

hmhbooks.com

Hand-lettering by Andrea Miller

Cover illustrations © 2021 by Geneva Bowers

Cover design by Andrea Miller

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Arnold, Marie, author.

Title: The year I flew away / by Marie Arnold.

Description: Boston : Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, [2021] | Audience: Ages 10 to 12. | Audience: Grades 4–6. | Summary: After moving from her home in Haiti to her uncle’s home in Brooklyn, ten-year-old Gabrielle, feeling bullied and out of place, makes a misguided deal with a witch.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019036630 (print) | LCCN 2019036631 (ebook) | ISBN 9780358272755 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780358273271 (ebook)

Subjects: CYAC: Moving, Household—Fiction. | Immigrants—Fiction. | Witchcraft—Fiction. | Friendship—Fiction. | Haitian Americans—Fiction.

Classification: LCC PZ7.1.A7632 Sum 2021 (print) | LCC PZ7.1.A7632 (ebook) | DDC [Fic]—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019036630

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019036631

v1.0121

For Haiti

&

the ones who struggle to belong

Chapter One

The River That Wasn’t There

IT TAKES HARD WORK to eat nine mangoes back to back, but that’s just what I’m going to do. I’m about to become mango champion of my village. My best friend, Stephanie, stacks a pile of mangoes in front of me. The boys assemble their stack in front of Paul, the boy I will be racing against. This match has been a long time coming. All the kids in the village put off their chores to watch us.

My heart is beating loud and fast, like a drum at a carnival. I look over at Paul. He’s taller, bigger, and quicker than me. But today is not his day; it’s mine. I’ve been practicing. I turn and nod to Stephanie; she smiles back at me. We are ready.

All the kids shout, “One, two, three—eat!”

I bite into my first mango—it tastes like honey and summer. It oozes out sticky-sweet nectar that runs down my fingers. I tear into another with my teeth, suck all the juices out, then toss the skin aside and start on a new one. While the boys laugh and make fun of me for even trying to beat Paul, I rip into my third mango.

Paul is showing off by juggling some of the mangoes before he eats them. He’s so sure that he’ll win that he takes time to joke around. But I’m not joking around. This is serious. I’m on my seventh mango. Soon, the boys notice that I am ahead and close to winning. That’s when they call out to Paul and demand that he eat faster.

“She’s a girl! You can’t let her win!” the boys shout.

“Hurry, Gabrielle! Hurry!” Stephanie shouts.

Paul speeds up—he’s like a hungry animal. I’m on my last mango, but Paul is close to catching up with me.

“You can do it!” The girls cheer as my victory gets closer. I bite and chew through the last mango, just as Paul is about to finish his. It’s close—but not close enough. I toss aside the final mango skin, and it lands in the bucket before Paul’s mango does—I win!

“Yay!” Stephanie and I rejoice with the other girls.

“Gabrielle Marie Jean, you better not be in another mango contest!” My mom’s voice rings throughout the village. The crowd scatters, everyone but Stephanie.

“You better not be staining that dress, it’s one of your good ones . . .” my mom says. I can’t see her yet, but her voice fills up the village. She’s getting closer. I look down at my dress, and it’s dripping with mango juice and dirt.

“Ah, we gotta go!” I say to Stephanie as I grab her hand. We run off and head to our favorite hiding place—the crawlspace under the church. We wiggle our way inside and lie flat on our stomachs. We look out at the parade of shoes and sandals going by us.

We hear my mom asking other grownups where I am. They all tell her they don’t know. My mom calls out my name. Judging by her tone, I’m really in for it.

“We can’t hide here forever,” Stephanie says.

“Maybe we hide just long enough for my mom to find something else to be mad about.”

“Okay, but you are usually the reason she’s mad, so . . .”

Stephanie’s right. I am usually the one who makes my mom use her I’m-not-happy-with-you face. And yes, sometimes I do get into trouble, but it’s mostly not my fault. Like, it’s not my fault that I like competing against the boys. They think that because they are boys they can do everything better. So it’s up to Stephanie and me to show them girls can do stuff too. Also, it’s not my fault that mangoes are so good that I have to eat them all.

“Gabrielle, you have three seconds to come out from wherever you’re hiding!” my mom warns as we watch her red sandals get closer. Stephanie and I look at each other with wide eyes.

“Go, save yourself,” I tell her.

“I can’t leave you here alone,” she replies.

“It’s too late for me. Go!”

“Okay. Good luck,” she says as she crawls out of our hiding spot.

I hear footsteps approaching. I see red sandals head toward me and then stop. Mom knows I’m under here. But she doesn’t scold me or yank me out from under the crawlspace. Instead, she sits at the base of the steps.

“Well, I can’t find my daughter. I guess I better get a new one. One who doesn’t get mud and mango juice all over her dress. One who finishes her chores before she goes to play. But even if this new daughter is perfect, I’ll still miss the one I had before. The one who gave the best hugs and made me laugh. The daughter who almost won a mango contest.”

“Almost?” I shout in disbelief. I crawl out from under the church to defend my championship. I stand before her. “Mom, I won, I really won!”

“Yes, I know,” she says as she stands up.

That’s when I realize . . . “Hey, you tricked me!”

“Moms are allowed to trick their kids. Now, explain yourself. You are a mess, young lady!” she says.

“I know, I’m sorry, but I had to compete.”

She looks me over, but this time she twists her lips from side to side. I think that means she’s thinking.

“Am I in trouble?” I ask.

“Well, that depends. Who did you beat out to win the mango contest?”

“Paul.”

“He’s twice your size!” she says with a big grin. She quickly changes her expression, like she just remembered she was supposed to be upset. “You should be grounded this evenin

g. Which is a shame, because guess whose bones have been talking?”

“Madame Tita?” I ask as I start jumping up and down.

Madame Tita is a round woman with pretty skin, like midnight. She wears colorful wraps on her head and moves like a turtle. Her voice is deep and rumbles. She sounds like what mountains would sound like if mountains had a voice. She’s one hundred years old, and what she says goes because she’s the oldest. When her bones ache a little, she says they’re talking to her. And when her bones speak, it usually means it’s going to rain!

Rain is even better than mangoes. When it rains, it’s playtime for us kids. The adults have to work by gathering the water and storing it to use later. And here’s the best part—our parents let us play, jump, and dance in the rain. That way, we get clean without having to use the water they saved up.

“Madame Tita said it’s going to rain?” I ask.

“Yes. Her bones have spoken; rain will come soon. I’ll let you play in it, but only if you promise no more mango contests.”

“But Mom . . .”

She places her hands on her hips and tilts her head to the side. Uh-oh, head tilting is never good.

“You have to make a decision. Rain or mangoes?” she says.

“Rain.”

She smiles. “I had a feeling you’d say that.”

“Mom, I worked really hard to win today. And I did. So, if I work hard to get something, does that mean I will always get it?” I ask.

She bends down so that our eyes meet, and she moves one of my braids away from my face. “Gabrielle, if you work hard and do your best, there’s nothing you can’t do.”

“Can I fly a plane?”

“Yes, you can do that.”

“How?”

“Well, first you have to go to school to learn all about planes.”

Something makes my heart hurt, and I hold on to my chest and look down at the ground.

“What is it, Ba-Ba?” my mom asks, calling me by my nickname.

“We don’t have money to send me to airplane school.”

“Gabrielle, you are a kid. And as a kid, you have only one job: dream the biggest dream you can. And your dad and I will try to help you make that dream come true.”

“Even airplane school?”

“Yes, even airplane school.”

“Okay, I guess . . .” I reply.

She looks at my lips. “Oh no, are you pouting?” she says with a smile.

“No, no, I’m not pouting!”

“It’s too late, I saw you pouting. You know what that means . . . spider fingers!”

She wiggles her fingers and starts tickling me. I squirm and wiggle uncontrollably as I laugh. She tickles me again and again. Everyone in the village can hear my laugh because it’s a super laugh. The kind you can’t stop even when you try really hard.

“Okay, okay. I’m not pouting anymore, Mom.”

She stops tickling me and hugs me extra tight. When the hug is over, there are tears in her eyes.

“What’s wrong, Mom?”

She blinks them away quickly. “Ba-Ba, your dad and I . . . we love you.”

“Mom, I already know that. The sky is changing colors. It’s all gray. The rain is coming. Can I go play now, please?”

She laughs softly, shakes her head, and says, “Go get your bathing suit and the soap.”

I zip back to our house, quickly put on my bright yellow bathing suit, and rub soap all over myself. I run out to the front porch. The air is cold, and thunder rumbles in the sky.

It’s coming . . . it’s coming . . . BOOM! The sky opens up, and it starts to rain. It’s raining so hard, it’s like the sky is arguing with the earth.

“It’s here! It’s here!” I yell.

There are kids already playing in the rain. Darn it, I’m late! Stephanie is in her red bathing suit, calling for me to come and get wet with her. A few houses away, Paul signals he wants to race. I’m ready! I run off the porch, but Mom stops me because I forgot to rub soap behind my ears and behind my neck.

“Aw, Mom!” I say as she rubs the soap behind my ears. When she’s done, I run out to the center of the village with my friends and shout, “Here’s the rain! Here’s the rain!” And we take off running. We zoom through the village with our hands held up high in the air. We open our mouths wide and swallow plump drops of rain. We race. We dance. We laugh.

When our parents finally drag us back inside, the rain has gone and night is falling. I get ready for bed, but not really, because tonight is the first of the month. And every first of the month, the grownups gather in the center of the village and tell ghost stories. This time they are telling stories on the front porch of Madame Tita’s house because the center of the village is still full of muddy water.

I love, love, love story time. I’m not talking about bedtime stories with happy endings. I’m talking about grown-up story time with real-life tales of ghosts and creatures of darkness.

We aren’t allowed to listen to the stories. The grownups always send us to bed. But going to bed and staying in bed are two different things. So on story night when my mom says, “Gabrielle, it’s bedtime,” I do as she says and lie down. But then I get up, and so do all my friends. We sneak into the center of the village and overhear the best and scariest stories ever told.

There are tales of witches who take your smile away for good if you back out of a deal, or warlocks who take your breath in the night if you wrong them.

My favorite stories are always the ones about people going on adventures. They face impossible tasks and deadly foes. Sometimes the people in the story lose an ear in battle or leave behind a finger or even an eyeball. It’s gross and creepy; in other words, it’s awesome!

When I take in the stories, I get so caught up in the adventure that I sometimes forget to blink or breathe. Stephanie has to poke me in the ribs, and only then do I let the air back into my lungs. She saves my life once a month.

I think story time should be all the time. But as soon as the sun comes up, it’s back to chores. My friends and I have to help out our families by fetching water from the well, which is really far away. We have to sweep and mop the floors. We walk to the market and sometimes carry baskets of food on our heads under the blazing-hot sun. Going to the market is hard, but not going at all is worse. That means your family doesn’t have enough money for food.

Some of my friends’ families are split apart because the parents can’t afford to keep any more kids. So they send some of their kids off to live with relatives in other villages. Some of the people I know don’t own shoes and have to ask a neighbor for something to wear on their feet. The people in my village come together, and we help each other with food and clothing.

Also, we don’t always have electricity. We have to use gas lamps or candlelight. The meat at the market is expensive, and often we have to go without it. And lately, even the rice has gotten costly. Sometimes we eat cornmeal porridge instead, because a handful of it makes a pot big enough to feed two families.

Most of the grownups in the village are merchants, including my parents. It’s hard because the road they have to take to the market is unpaved, rocky, and often full of mud. It takes them forever to get to the market and forever to get back home.

The absolute worst part of my homeland is violence. It comes from a group of soldiers with unlimited power called Macoute. They are tall and thin, like pencils. They wear tan, ugly uniforms and even more hideous hats. They enter villages and trample over everything. They take people away, and their families never see them again. And if you try to resist, the Macoute will hurt you.

They came one night for Stephanie’s brother, Jean-Paul. We tried to hide him and help him get away, but they found him. They hit him over and over until he didn’t move anymore. We had a funeral, and everyone cried. Stephanie’s mom, Mrs. Almé, cried the hardest and the longest.

Ever since then, every night I walk by Mrs. Almé’s bedroom, I see the shadow of a flowing river. It’s a river sh

e made with her tears. I call it Night River because it only exists at night. Tonight, I see the Night River, but this time, Mrs. Almé is drowning in it. I can smell the salt in the water and feel the heaviness of her body as it begins to sink to the bottom. I rush inside her house.

I was right. The Night River overflowed and threatened to carry her away for good. Everyone in the village comes to see what is happening. But all they see is Mrs. Almé with her eyes closed, twisting and twitching out of control. They can’t see the river.

“Madame Tita, I know what’s wrong!” I shout.

“Then help her, Gabrielle!”

Suddenly, I’m standing on a bluff. Below me is the raging, wrathful river. The wind howls in my ears and the cold air whips through my nightgown. It makes my whole body tremble. Mrs. Almé’s body is being picked up and thrown around by the current. She’s going under!

Not if I can help it!

“Night River, you can’t have her!” I shout as I leap off the bluff and down into the abyss.

The river fights me, but I stay strong. I wrestle and punch at the waves. I dive deeper and deeper down into the freezing river. I see Stephanie’s mom. She is about to sink into the floor of the river. I swim down to her and latch onto her nightgown. Together we head toward the surface. Suddenly, something with tentacles grabs hold of her ankle and wraps around it.

I know what the creature is—an octopus. But not just any kind of octopus. This one feeds on loss and loneliness. But I won’t let it get her. I hold her face in my hands and concentrate. I focus on the one thing that could fight off the creature—memory.

I place all the memories of Stephanie and her family in my eyes. Mrs. Almé sees the images reflecting in my eyes like a moving photo album. She starts to remember all the people who love her. She kicks the creature in the face—hard. It lets go, and together we burst through the surface of the water.

In a flash, the river dries up, and we are back in Mrs. Almé’s bedroom, breathless and soaking wet. She pulls her daughter close and hugs her for a long time.

Later, I ask my mom why I was the only one who saw the river. She says I’m sensitive and have a gift—I’m able to see what others typically don’t.

The Year I Flew Away

The Year I Flew Away